Everyone has heard the advice: “Drink eight glasses of water a day.” It’s become almost a mantra in health and wellness circles. But is it really the golden rule for everyone? Many experts say no — hydration needs vary based on activity, climate, individual physiology, diet, age, health status, and so forth. The “8-glasses” guideline is a useful starting point, but it can be too simplistic. This article explores what the research says about hydration, what factors influence how much fluid we need, what happens when we underhydrate or overhydrate, and practical tips for staying well-hydrated in a smarter, more personalized way.

The Origin of the “8 Glasses” Rule & Its Limitations

- The idea of drinking “eight 8-ounce glasses” (about 1.9 liters) has been popular for decades, but its scientific origin is murky. Some sources trace its roots to advice from health boards in the mid-20th century, which also noted that many people get fluids from foods. However, over time, the nuance got lost, and the phrase “8 glasses of plain water” became common.

- Harvard Health points out that many people consume sufficient fluid from a combination of water, other beverages, and food. The requirement of “8 glasses of plain water” is not strictly required for everyone.

- Health authorities in different countries provide guidelines that are more nuanced. For example, the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine suggest total water intake (from all beverages and food) of about 3.7 liters per day for men and 2.7 liters per day for women under normal conditions.

Thus, while “8×8” is a helpful heuristic, it does not suit everyone equally.

What Determines Hydration Needs

Our hydration needs depend on many interacting factors. Understanding them helps us tune our hydration habits better.

| Factor | How it Influences Water Needs |

|---|---|

| Activity level / Exercise | Physical activity increases fluid loss through sweat and respiration. For someone who exercises heavily, hydration needs are much higher. Rarely is “8 glasses” enough for athletes. |

| Climate & Heat | Hot, humid or arid climates cause more sweating and faster water loss. Elevation and dry air also matter. Someone living in a hot zone or working outdoors will need more fluid. |

| Dietary Contributions | Many foods — fruits, vegetables, soups — contain water. For many people, about 20% of daily fluid intake comes from food. |

| Age | Children often have higher water content per body weight; elders may have reduced thirst sensation. Older adults are more vulnerable to dehydration. |

| Health status / Medical Conditions | Conditions like kidney disease, diabetes, fever, vomiting/diarrhea, and some medications (diuretics, etc.) can increase fluid needs or complicate hydration. |

| Pregnancy / Breastfeeding | Pregnant and lactating individuals typically require more fluids. Physiological changes increase water needs. |

How Much Fluid Is Enough? What Research Suggests

Recent studies have attempted to pin down more precise markers of optimal hydration, often using urine concentration (osmolality) or other biomarkers, in addition to self-reported fluid intake.

- One study of healthy adults in the U.S. found that to maintain a 24-hour urine osmolality below ~500 mmol/kg (a marker of optimal hydration), men needed about 3.39 liters per day, and women about 2.61 liters per day of total water intake.

- The Institute of Medicine’s guidance (as above) of ~3.7 L/day for men and ~2.7 L/day for women covers most people in mild environmental conditions.

- For those who are physically active or exposed to heat, fluid needs can increase significantly. Hydration for athletes includes not just replacing water, but also electrolytes lost in sweat.

Risks of Dehydration

Even mild dehydration can have meaningful effects. Some key risks and warning signs:

- Losses as small as 1-2% of body water can lead to fatigue, reduced concentration, mood changes, decreased performance, headaches.

- More severe dehydration (from illness, heat exposure, heavy sweating, or disease) can cause dizziness, confusion, low blood pressure, kidney stress or injury, and in worst cases, organ failure.

- Vulnerable populations (elderly, infants, people with chronic disease) are at greater risk both because of physiologic changes and sometimes because they might not perceive or act on thirst properly.

Risks of Overhydration

While dehydration often gets more attention, overhydration (or excessive fluid intake in some situations) can also be dangerous. Key issues include:

- Hyponatremia: When water dilutes body sodium levels too much; this can lead to swelling, including of brain cells, seizures, and in rare cases, death. Athletes who drink large volumes without balancing electrolytes are at risk.

- Water Intoxication: Symptoms like nausea, vomiting, headache, confusion, in severe cases coma. It’s rare, but does happen in certain conditions like endurance sports or where people overdrink in a short time.

- Electrolyte imbalance and issues for kidneys and heart if fluid intake is extreme relative to how much the body can process.

Signs of Good Hydration vs Warning Signs

To manage your hydration well, it helps to know what to watch out for — both good signs and red flags:

Good signs:

- Urine that is pale yellow (“lemonade” color) most of the time. — not dark, not totally transparent.

- Feeling generally energetic, not fatigued or dizzy.

- Regular urination; not holding on for too long.

- Skin that is well hydrated (not overly dry).

Warning signs of underhydration:

- Thirst, dry mouth, cracked lips.

- Dark yellow or strong-smelling urine.

- Decreased urine output.

- Fatigue, headache, lightheadedness.

- In more severe cases: confusion, rapid heart rate, low blood pressure.

Warning signs of overhydration:

- Swelling in hands, feet.

- Nausea, vomiting.

- Confusion/disorientation.

- In extreme cases, seizures.

Hydration in Special Situation

Certain situations require paying extra attention to hydration:

- During Exercise/Athletics: Before, during, and after physical activity, fluid and sometimes electrolyte replacement is essential. Sweat loss can be significant. Sports drinks or electrolyte‐infused beverages may help when exercising long durations or in heat.

- Heat/Hot Environments: High temperatures increase sweat loss. Humid air reduces evaporation, making it harder to cool down. Staying ahead of thirst is useful in such cases.

- Illness: Fever, vomiting, diarrhea all cause fluid and electrolyte loss. In those cases, rehydration (ideally with fluids that include electrolytes) becomes critical.

- High Altitude: When at altitude, the body loses more water via respiration and other means; fluid needs can increase.

- Pregnancy & Breastfeeding: Increased blood volume, fluid shifts, milk production — all this increases fluid demand.

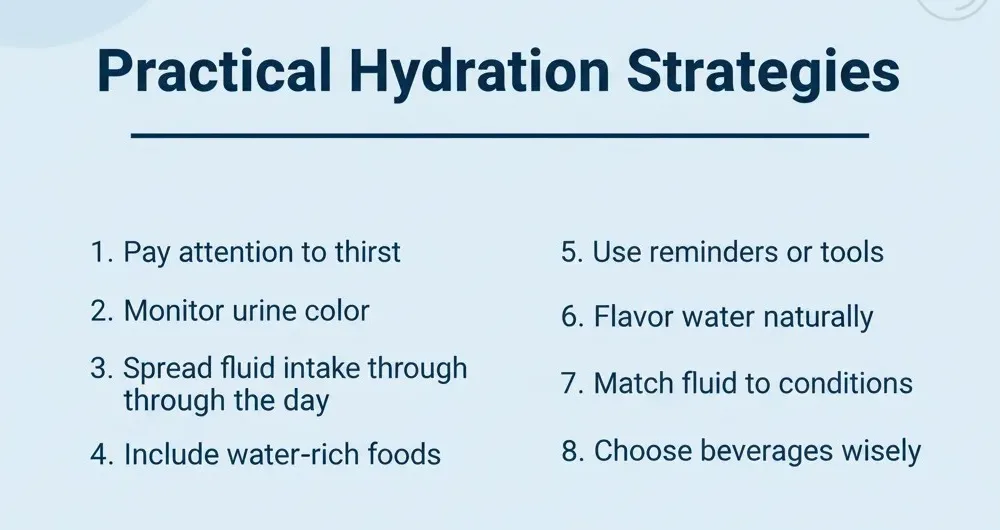

Practical Hydration Strategies

Instead of rigid rules, here are flexible strategies to help maintain good hydration:

- Pay attention to thirst — your body has built-in signals. Don’t ignore them.

- Monitor urine color — a simple, rough check. Pale yellow is good. Darker = drink more.

- Spread fluid intake through the day — sip often rather than gulping large amounts at once.

- Include water-rich foods — fruits like watermelon, cucumbers, lettuce, soups help add fluids.

- Use reminders or tools — reusable water bottles, apps, setting goals (e.g. drink a glass with each meal).

- Flavor water naturally — lemon, cucumber, mint to make water more appealing if plain water feels boring.

- Match fluid to conditions — more fluids during heat, when exercising, or when ill; also when pregnant or breastfeeding.

- Choose beverages wisely — water is best; but drinks like tea, coffee, unsweetened plant milks count. Limit sugary beverages.

How Much Is “Too Much”? Safe Upper Limits

While overhydration is rare in everyday life, certain scenarios carry increased risk. Some general guidelines for safe upper limits:

Generally, healthy kidneys can process up to ~0.8-1 liter/hour of water under normal conditions. Drinking far above that in a short span can overload the system.

- Be especially cautious with large volumes of water during endurance exercise without electrolyte replacement.

- Make sure electrolyte balance (notably sodium) is maintained when fluids are high.

Myths & Misconceptions

- “Coffee and tea dehydrate you.” Reality: They do contribute fluids. Unless consumed in extreme amounts, their mild diuretic effects are offset by the fluid they provide.

- “You must force yourself to drink 8 full glasses even when not thirsty.” Actually, drinking to thirst plus a bit more during heat or exertion tends to work well.

- “All fluids are created equal.” Not exactly: fluids with high sugar or alcohol content can have unintended metabolic or diuretic effects.

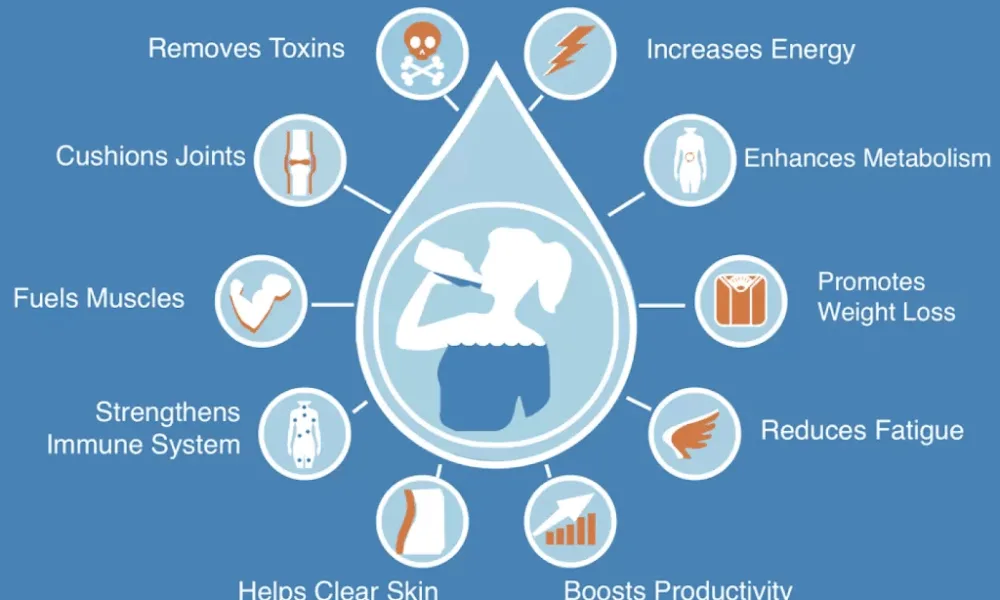

Benefits of Good Hydration

What do we gain when hydration is optimized (not under, not over)?

- Better physical performance – reduced fatigue, quicker recovery, better endurance.

- Cognitive benefits – sharper focus, better mood, less irritability.

- Health benefits – better kidney function, lower risk of kidney stones, better regulation of body temperature.

- Improved digestion: helps in smooth transit, avoids constipation.

- Skin and appearance: hydrated skin tends to look better, less dullness.

Case Examples & Real-World Evidence

- Studies on workplace performance show even mild dehydration can reduce productivity and increase errors.

- Athletes who hydrate well (including electrolytes when needed) recover faster and avoid heat-related illnesses.

- Epidemiological data show that in hot climates or during heat waves, dehydration contributes to hospital admissions.

Personalized Hydration: How to Figure Out What’s Best for You

To move beyond “8 glasses” to something that works for you:

- Track your fluid intake for a few days—including beverages and water-rich foods. See how you feel: energy, thirst, urine color.

- Note your environment, activity, health: if you’re sweating, getting sick, in higher temperatures, increase fluid intake.

- Adjust for special conditions: pregnancy, breastfeeding, age, disease, medications.

- Feel for signs of imbalance (thirst, fatigue, cramps, swelling) and adjust.

- Use tools or wearables: Some newer technologies are being developed that non-invasively monitor hydration (skin sensors, urine markers, etc.). Early promise in “Internet of Medical Things” for dehydration monitoring.

Conclusion

“Hydration” isn’t a one-size-fits-all topic. Yes, the “8 glasses a day” guideline has value because it raises awareness. But true hydration is a dynamic balance. It calls for listening to your body, observing your environment, understanding your lifestyle, and adjusting accordingly. When done well, good hydration supports all aspects of health — physical performance, mental clarity, organ function, and overall well-being.

So next time you think about drinking water, go beyond the number.

Ask: Why do I need this much today? How active will I be? How hot is it? What else am I eating or drinking?

That’s how you build hydration habits that truly serve you — not just a rule written down somewhere.